近日,日本前财务副大臣、哥伦比亚大学国际与公共事务学院的教授伊藤隆俊(TAKATOSHI ITO)发表了一篇文章,分析了为什么日本经过“失去的三十年”后,至今依然难以走出衰退阴影,以至于去年经济进一步落后德国至全球第四位。作者指出,日本老龄化和劳动力紧缺,以及科技创新的长期停滞是拖累经济的难解痼疾,政府必须尽快制定相应战略,重振日本经济。

哈佛大学教授傅高义(Ezra Vogel) 1979年出版的《日本第一:美国的教训》一书在日本迅速成为畅销书。这个讨好的标题当然有助于销售,但真正引起轰动的是这本书的核心论点——日本的治理和商业方式优于其他国家。

当时,日本正在腾飞。在20世纪50年代和60年代的大部分时间里,其国内生产总值每年增长约10%,在70年代后半期增长4-5%,这一趋势将持续到整个80年代。但日本商人和政治领导人不确定日本在经济上的成功是否真的因为其独特的制度。但尽管如此,对他们来说,傅高义的书相当于一种认可,强化了日本很快就会超越美国成为世界最大经济体的信念。

在随后的几年里,日本似乎正在朝着这个目标前进。20世纪80年代后半期,日本股票价格上涨了两倍,实际资产价格上涨了四倍。1988年,日本的国内生产总值相当于美国的60%(以当前美元计算),人口约为当时的一半,其人均国内生产总值明显更高。1995年,日元大幅升值后,日本经济规模约为美国经济的四分之三。

事实证明,这是日本的“巅峰”。很快,日本经济陷入了长达数十年的停滞和通货紧缩。1995年至2010年,日本国内生产总值出现负增长(以日元计算)。

与此同时,美国经济以每年2%左右的速度增长,而中国则年复一年地实现了两位数的增长。如今,日本的GDP仅为美国的15.4%,而自2010年以来,中国的GDP一直高于日本。日本非但没有上升到第一位,反而下降到了第三位。

中国已超过日本成为世界第二大经济体的消息,并没有引起日本公众的强烈抗议,日本公众似乎对其经济的衰退听天由命。可以肯定的是,日本选民在前一年让反对党日本民主党(DPJ)战胜了长期占据主导地位的自民党(LDP)。但与民主党的蜜月期并没有持续太久。该党在治理、外交和经济政策方面都远远落后,从2009年到2012年,民主党总理的每人任期只持续了不到一年的时间。

在2012年12月的选举中,日本选民尝试了一种不同的方法,第二次选举自民党的安倍晋三为首相。安倍迅速推出了一项名为“安倍经济学”的大胆经济政策,旨在通过“三支箭”最终使日本经济摆脱20年的通货紧缩和衰退,也就是大规模货币宽松、扩张性财政政策和长期增长战略。

安倍的计划在一定程度上奏效了。得益于日本央行的货币扩张,日本最终实现了正通货膨胀率。但由于人口快速老龄化,实际增长仍然阴晴不定。尽管劳动生产率显著提高,但这些增长不足以抵消工人数量和工作时间的下降。再加上2012-2014年日元贬值,日本的GDP(以美元计算)在趋于平稳之前有所下降。

现在,日本的衰落更加严重:去年,德国超过日本,成为世界第三大经济体。然而,公众对日本全球地位下降的消息再次只是耸耸肩。那种能够刺激政府进行动态性改革的建设性愤怒情绪,在日本公众中已经看不到了。

图:日本连续两个季度GDP都出现了负增长

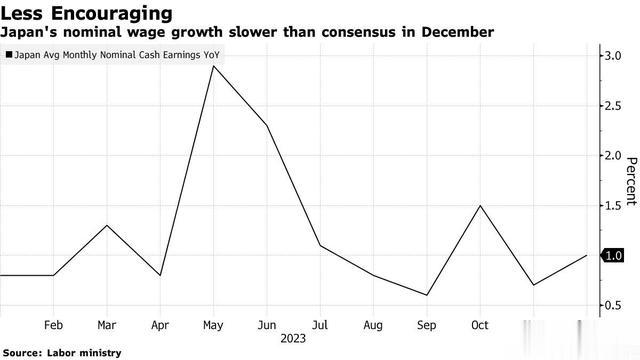

图:12月日本名义工资增长率低于预期值

振兴日本经济所需的措施清单既冗长又众所周知。例如,日本必须引导居民银行存款和机构储蓄转向投资于股票和其他替代品。此外,由于人口规模趋于下降,每个部门都迫切需要提高生产力,而这一点必须通过更加积极的数字化来实现。

与此同时,目前的劳动力短缺应该会推高名义工资,对商品和服务的强劲需求以及投入成本的上升应该反映在更高的价格上。这在日本是一门被遗忘的艺术:在几十年的通货紧缩中,价格机制实际上变得不起作用。相对价格和绝对价格冻结,资源配置受到影响。

好消息是,“通缩心态”正在改变,尤其是因为日本央行近两年来一直设法将通胀率保持在2%的目标之上。但超宽松的货币政策会带来高昂的成本。与美国的利差不断扩大,2022-23年利率迅速上升,导致日元兑美元迅速贬值,从2022年1月的115日元贬值到10个月后和整个2023年的150日元。

但是,尽管日元相对于美元的贬值可能导致了日本以美元计算的GDP下降,但这并不是全部。毕竟,疲软的货币往往可以通过提高出口竞争力来促进经济增长。但在日本没有这种迹象,这反映了一个更深层次的问题:创新和生产都在很大程度上离开了日本。日本支付给美国IT服务公司的款项增长迅速,推高了进口额。日本必须采取紧急和果断的步骤扭转这一趋势,例如通过促进科学和技术教育,在国内生产信息技术服务。

图:日本经济在私人消费和私人投资领域都出现连续两个季度的负增长后,经济走向了衰退的边缘,出口是唯一的亮点

如果经济跌至第四位还不足以唤醒日本,那么它很快就会跌至第五位。国际货币基金组织预计,印度的国内生产总值将在2026年超过日本(按美元计算)。为了避免进一步的衰退,日本政府必须制定一个明确的战略,提高生产力,扩大劳动力,并将稀缺劳动力分配到生产力最高的部门。

英文原文如下:

Japan as Number Four

Takatoshi Ito, a former Japanese deputy vice minister of finance, is a professor at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and a senior professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo.

Feb 27, 2024TAKATOSHI ITO

Headlines confirming that Germany surpassed Japan last year as the world’s third-largest economy should serve as a wake-up call. Unless policymakers embrace far-reaching productivity-enhancing reforms, the country’s global position will continue to decline.

TOKYO – Harvard Professor Ezra Vogel’s 1979 book, Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, became an instant bestseller in Japan. The flattering title certainly helped sales, but it was the book’s central argument – that the Japanese approach to governance and business were superior to others – that really made a splash.

At the time, Japan was riding high. Its GDP had grown by about 10% annually for most of the 1950s and 1960s, and 4-5% during the second half of the 1970s – a trend that would continue throughout the 1980s. But Japanese businessmen and political leaders were not sure whether Japan had succeeded economically because of its unique system or despite it. For them, Vogel’s book amounted to a kind of seal of approval and reinforced the belief that Japan could soon surpass the United States to become the world’s largest economy.

In the years that followed, Japan appeared to be progressing toward this goal. In the second half of the 1980s, Japanese stock prices tripled, and real asset prices rose fourfold. In 1988, Japan’s GDP amounted to 60% that of the US (in current dollars), and, with a population about half the size at the time, its GDP per capita was significantly higher. In 1995, following a sharp appreciation of the yen, Japan’s economy was about three-quarters the size of the US economy.

That turned out to be “peak” Japan. Soon, the economy was gripped by decades-long stagnation and deflation. From 1995 to 2010, Japan experienced negative GDP growth (in yen terms). Meanwhile, the US economy grew by around 2% annually, and China racked up year after year of double-digit growth. Today, Japan’s GDP amounts to just 15.4% that of the US, and China’s GDP has been larger than Japan’s since 2010. Far from rising to number one, Japan fell to number three.

The news that China had surpassed Japan as the world’s second-largest economy did not prompt much of an outcry from the Japanese public, which appeared practically resigned to their economy’s decline. To be sure, Japanese voters had handed the opposition Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) a victory over the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) the previous year. But the honeymoon with the DPJ did not last long. The party fell far short on governance, diplomacy, and economic policy, and from 2009 to 2012, a parade of DPJ prime ministers each lasted barely a year in the position.

In the December 2012 election, Japanese voters tried a different approach, electing the LDP’s Abe Shinzō as prime minister for the second time. Abe quickly introduced a bold economic-policy package – dubbed Abenomics – that aimed finally to lift the Japanese economy out of two decades of deflation and recession with three “arrows”: massive monetary easing, expansionary fiscal policy, and a long-term growth strategy.

Abe’s plan worked – to a point. Thanks to the Bank of Japan’s monetary expansion, Japan finally achieved a positive inflation rate. But real growth remained elusive, owing to rapid population aging. Though labor productivity increased significantly, the gains were insufficient to offset the decline in the number of workers and working hours. Add to that yen depreciation in 2012-14, and Japan’s GDP declined (in US dollar terms), before flattening out.

Now, Japan has fallen even further: last year, Germany surpassed Japan as the world’s third-largest economy. And, once again, the public reaction to the news of Japan’s declining global position has amounted to a shrug. The kind of constructive anger that can spur dynamic reform is nowhere to be seen.

The list of measures needed to revitalize the Japanese economy is as well-known as it is long. For example, Japan must steer personal bank deposits and institutional savings to equities and alternatives. And productivity increases are sorely needed in every sector – an imperative that should be pursued through aggressive digitalization, given declining population size.

In the meantime, today’s labor shortages should drive up nominal wages, and strong demand for goods and services, as well as the rising costs of inputs, should be reflected in higher prices. This is something of a forgotten art in Japan: over decades of deflation, as consumers turned on companies that raised prices, the price mechanism became practically nonoperational. Relative and absolute prices froze, and resource allocation suffered.

The good news is that “deflationary mindsets” are changing, not least because the BOJ has managed to keep inflation above its 2% target for nearly two years. But ultra-accommodative monetary policy carries high costs. The growing interest-rate differential with the US, where rates rose rapidly in 2022-23, contributed to the yen’s rapid depreciation against the dollar, from ¥115 in January 2022 to ¥150 ten months later and throughout 2023.

But while the yen’s depreciation vis-à-vis the US dollar might have contributed to Japan’s declining GDP in US dollars, it is not the whole story. After all, a weak currency can often boost growth by making exports more competitive. But there is no sign of this in Japan, which reflects a deeper problem: both innovation and production have largely left the country. Payments to US IT-service companies are rising fast, pushing imports higher. Japan must take urgent and decisive steps to reverse this trend, such as by promoting science and technology education to generate IT-service production domestically.

If the economy’s fall to number four is not enough to wake Japan up, it will soon fall to number five. The International Monetary Fund projects that India’s GDP will overtake Japan’s (in dollar terms) in 2026. To stave off further decline, Japan’s government must devise a clear strategy for raising productivity, expanding the workforce, and allocating scarce labor to the most productive sectors.

原文链接:

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/japan-decline-to-fourth-largest-economy-wake-up-call-for-policymakers-by-takatoshi-ito-2024-02